Carly Hood, MPA, MPH

Population Health Service Fellow 2012-2014

Wisconsin Division of Public Health

Health First Wisconsin

Wisconsin Center for Health Equity

Madison, WI

As I wrap up my final week as a Wisconsin Population Health

Service Fellow, not only am I dedicating time to ensuring projects are complete

and my desk(s) are clean, but I’m making time to reflect on what the last 2

years as a fellow (and 4 as a Wisconsin citizen) have meant to me. I moved here in the summer of 2010 as a

reverse-culture-shocked graduate student, ready to apply what I had most

recently seen in Vietnam as student of public policy at the

Robert M. LaFollette School of Public

Affairs. As a “fighting Bob” I took classes in public management, policy

analysis, policy-making process and advanced statistics. And ate it up! I can

see now, I was most definitely at a point in my life where school sounded right

(boy, that ship has sailed!) But it was here that I also began seeing my lens

take shape, my interests honed. I observed that the policies I chose to

analyze, the experiences I brought to class to discuss, and the data I wanted

to play with focused on health and access to what I had always seen as a human

right: opportunity to live a healthy life. I quickly learned about the dual

program with the

UW School of Medicine and

Public Health and added on an extra summer of epidemiology, social and

behavioral health, and health policy courses to obtain my Master of Public

Health and Global Health Certificate alongside my Master of Public Affairs

degree.

I was fortunate to have been told about the

fellowship

program early enough to apply and post-application submission, waited

anxiously to hear back from folks at the

Population Health Institute.

Finally, in late February, I received the call that helped shape my career path

and joined the 4 other fellows in my cohort summer of 2012. Since my graduate

research was based on food policy, I naturally found dual placement sites at

the

Division of

Public Health in the Chronic Disease Program and at

Health First Wisconsin. (I later added

my tri-placement at the

Wisconsin Center for

Health Equity). And then…Poof! 2 years disappeared!

As my fellowship is ending soon, I was recently asked, “What

do you think you’ve done as a fellow?” Wellllllllll (insert headscratch). Sometimes

I want to say, “What HAVEN’T I done?!” Other times I ask myself, “Have a done

ANYthing?” For most fellows, I believe it’s a difficult question to answer when

there aren’t particular milestones, expectations or deliverables like those

found in many other public health positions descriptions (besides the CALs of

course!) The concrete products of my fellowship (which I was interested in

hearing 2

nd year fellows talk about as an applicant and incoming fellow

so I’ll touch on here) are what I shared in my exit interview last week and

include the following: I developed 2 strategic evaluations both aimed at

increasing capacity for folks working with homeless, impoverished and/or

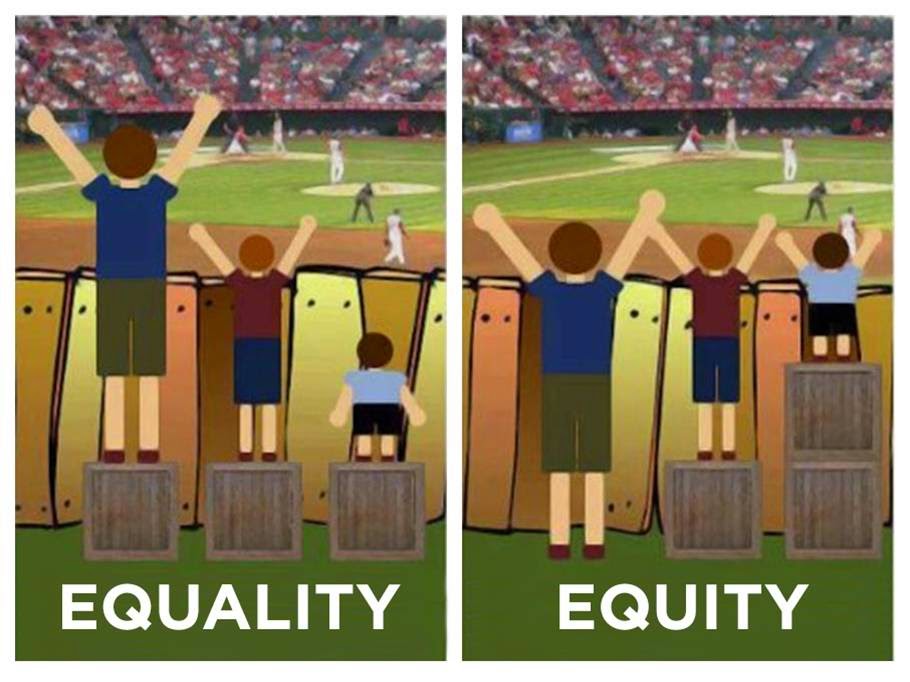

jobless individuals; I designed and implemented a year-long health equity

training at both placement sites; I analyzed socioeconomic data for a chapter

in the 2014

Healthiest Wisconsin

2020 Baseline and Health Disparities Report; I published

1

paper (2 in the works yet!), 2 Opinion pieces and 4 Letters to the Editor

in various Wisconsin media outlets; I led 2 years of discussion courses for

undergraduates interested in public health; I trained local and tribal health

departments around the state on the use of

national community health

tools; I presented on health equity/social policy in public health to

community groups, students, state public health employees, and national

audiences; and I developed

bi-monthly

resources on health equity and social policy for national partners.

While most of these have a tangible item attached to them (a

pdf report, a powerpoint presentation, a word document newsletter), some of

them do not. And in my eyes, the more important outcomes of all of these

projects have very little to do with the items one can see and touch. I have

found much more value in the relationships I’ve developed, the heightened understanding

of how public health & policy works at a State Health Department AND an

advocacy organization, and the confidence that my perspective is a valued and

impactful one.

I don’t believe in fate. I don’t think my career ‘required’

this 2-year experience or that I couldn’t also have been happy and successful

in another position (there are certainly positives and negatives to this

position). But I do believe that this experience gave me the flexibility and time to explore the many facets of public health, the plethora of

partners who are involved, and the varied organizations that support the field

of public health. I believe I was fortunate to be given the opportunity to hone the skills I wanted

and dump those I wasn’t interested in. And as an academically funded staff

person working in the field, I had access to more resources and training alternatives that helped me sharpen a sort

of ‘field of expertise.’

The fellowship was a great opportunity. And—like everything

else—it came with a fair share of challenges. I dealt with a loss of preceptors

(2 of mine left in the middle of my fellowship). I was conflicted with 2

placement sites and not feeling 100% a part of either. I was challenged to

assert the understanding that ‘fellow’ does not mean ‘student’ or

‘administrative assistant’—we are in fact highly trained professionals seeking

mentorship and experience early in our careers. And lastly, I struggled with

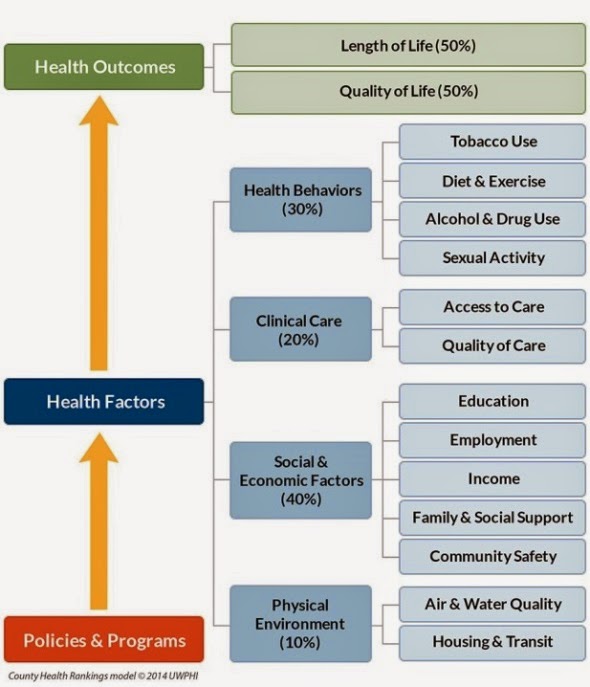

evolving interests, being originally interested in food policy my interests broadened

from issues of healthy food access to more upstream equity associated with

income, education and housing. That made projects at my particular placement

sites hard to find at times…but my preceptors were flexible and encouraging and

I was able to develop my own projects that focused on equity and increasing

capacity within my placement institutions. I was also able to expand many of my

projects to the

Wisconsin Center for Health

Equity, where I revamped the website and built several partnership that

results in facilitation and keynote speaking engagements.

In this way, the fellowship demanded innovativeness and

honesty. I had to be cognizant of the skills and abilities I wanted to develop, I had to be honest and open about those, and

then look for ways to infuse that work where I & my organizations were. In

contrast to many other positions, I had to speak up louder than I might

otherwise and was forced to be my own advocate. While this can be challenging at

first, it ultimately helped me learn who I was, what I wanted, and encouraged

me to think outside of the box. Today I feel lucky to have had the chance to

say, “Hey! This is what I want to

work on. How do we make that happen?”

In looking back over the last 4 years—and the fellowship in general—Wisconsin has provided a safe space for me to overcome my

reverse-culture shock, make new friends and professional connections, and build

on the amazing efforts of places like the

policy school (3

rd in the

country for Social Policy!), the

Institute for Research on Poverty, the

Population Health Institute, and the

School of Medicine & Public Health.

Due to its size and approachability (plus people’s lovely Midwestern demeanor!)

Wisconsin is a ripe place for networking and building connections. I will miss

those that I’ve made as I move on to a new position as Clinic & Public

Health Director for a

small clinic—in

a new country! But I feel more equipped to deal with the challenges I will

likely face in the developing world, and look forward to contrasting the public

health system in Belize with that of the United States and Wisconsin. Thank you

to the fellowship community for the support and learning you’ve provided me!!!!

I do hope you’ll keep in touch.