Evelyn Sharkey, MPH, MSW

City of Milwaukee Health Department

Wisconsin Division of Public Health

Madison, WI

“How can professionals dedicated to improving health continue our traditional roles of promoting healthy behaviors and delivering quality health care and also balance our repertoire by adding the skills, competencies, tools, and methods to address the socioeconomic policies, systems, and environments that so strongly influence health?” (p. 218)

Dr. Geof Swain, founding director of the Wisconsin Center for Health Equity, and former Fellows Katarina Grande (2010-2012 cohort), Carly Hood (2012-2014 cohort), and Paula Tran Inzeo (2010-2012 cohort) ask this question to frame their commentary published in the December 2014 issue of the Wisconsin Medical Journal, posing a dilemma that confronts physicians and other health care professionals on a daily basis as they care for patients.

|

| Determinants of health, from Dahlgren & Whitehead (1991), as cited in Exworthy (2008) |

Before

getting into the authors’ suggestions for overcoming this dilemma, let’s get

some background on the broader issues addressed in the commentary: health and the things that make people and

communities more or less healthy.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), health is more than

just not being sick; rather, it’s “a state of complete physical, mental and social

well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”1 Overall health is influenced by various

factors known as “health determinants,” which include not just health care, but

also genetics and biology, individual behaviors, social and economic

conditions, and the physical environment.2,3 Most of these determinants are “modifiable” in

the sense that it’s possible to change or control them, including health care,

individual behaviors, social and economic factors, and the environment. However, it’s not yet possible to

significantly alter an individual’s genetics and biology. It’s also important to note that many of

these determinants are external to an individual, including health care, social

and economic factors, and the physical environment.

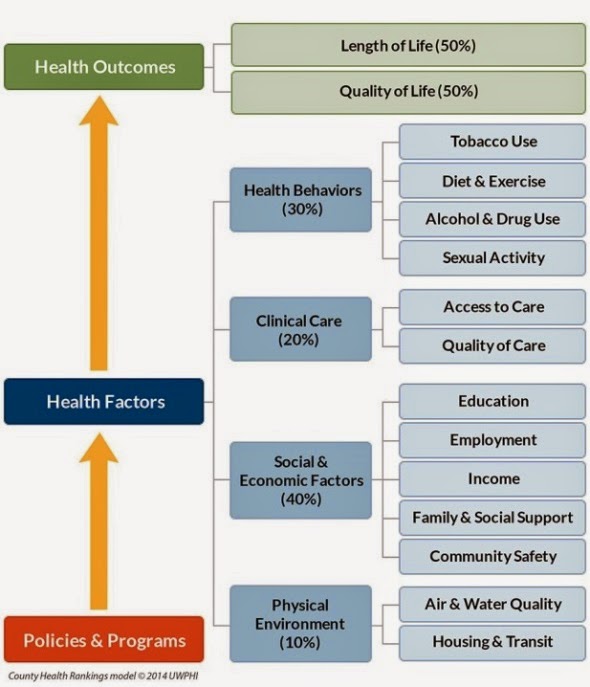

|

The Rankings model

of modifiable health

factors that impact community health

|

As Swain et al. point out, almost all of the health-related funding in the U.S. is geared towards improving access and quality of health care services. While health care is undoubtedly important, there is a great deal of evidence that social and economic factors and the physical environment may actually have a stronger impact on health. This is shown by one model of the impact of health determinants developed by the County Health Rankings & Roadmaps program. This program is a collaboration between the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, which created the model to estimate the relative contribution of modifiable health determinants.7 Biology and genetics are not modifiable and are therefore not included.

What does the Rankings model show? First, 50% of the modifiable factors that influence health are social determinants of health. If you dig deeper into this 50%, you can see that the influence of social and economic factors is especially strong, accounting for 40% of the factors that impact health. Based on this, it’s clear that people who seek to promote health should address these social and economic influences. However, according to Swain et al., there is limited guidance as to how physicians and other health care professionals and health systems can actually go about doing this. This may be why more than 80% of U.S. physicians think unmet social needs negatively affect health but do not feel capable of addressing the social needs of their patients.8

Through exploring two social determinants of health that have been studied extensively—income/employment and education—Swain et al. review evidence-based examples of both clinical and policy-level actions that health care professionals can take to address social determinants. They conclude their commentary by providing concrete and actionable suggestions and resources for addressing income/employment, education, and other socioeconomic factors that influence individual and community health. At the clinical level, the authors suggest health care professionals screen for socioeconomic issues like food and employment during clinical visits and coordinate their services with social workers, community health workers, and others. At the population level, suggested strategies include advocating for social and economic policies that promote health, working collectively with peers and professional associations; and being “both patient and persistent” (p. 220).

This is a helpful article for anyone interested in promoting the health and well-being of both individuals and communities, and it was excellent foundational reading for the fellowship’s February monthly meeting on health equity. Fellows were joined at this meeting by students from the TRIUMPH program. TRIUMPH, which stands for Training in Urban Medicine and Public Health, is a program for 3rd and 4th year medical students at UW Madison’s School of Medicine and Public Health. The program integrates clinical medicine with community and public health and aims to provide medical students with the knowledge and skills needed to promote health equity and reduce disparities.

During the meeting,

attendees learned about The National Equity Atlas, a new policy and data

tool that can be used to make the economic case for equity. The Atlas includes data from all 50 states,

Washington D.C., and the largest 150 metropolitan statistical areas in the U.S.

(including the Madison and Milwaukee metropolitan areas).

|

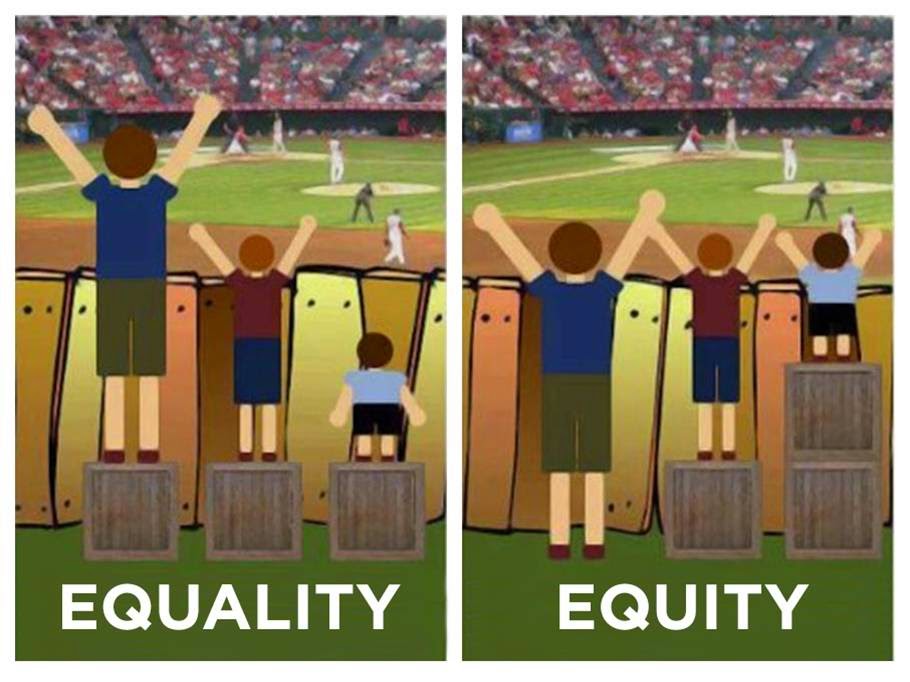

| A picture depicting

the difference between “equality” and “equity,” featured in the February meeting presentation by Angela Russell and Jordan Bingham. Source: City of Portland Office of Equity and Human Rights |

In

the afternoon, fellows and TRIUMPH students participated in an in-depth

conversation on health equity strategies for public health and medical

professionals led by Dr. Geof Swain. They wrestled with the difference between

equality and equity and discussed frameworks for thinking about how the social

determinants of health lead to health disparities. The day ended with an

engaging presentation by Angela Russell and Jordan Bingham, Health Equity

Coordinators from Public Health Madison Dane County, on how to talk to policy

makers about health equity.

Sources:

1WHO Definition of Health. World Health Organization Website. http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html. Accessed February 11, 2015.

2McGovern L, Miller G, Hughes-Cromwick P. Health Policy Brief: The Relative Contribution of Multiple Determinants to Health Outcomes. Health Affairs. August 21, 2014. http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=123. Accessed February 11, 2015.

3The Determinants of Health. World Health Organization Web Site. http://www.who.int/hia/evidence/doh/en/. Accessed February 11, 2015.

4 Healthy People 2020. Social Determinants of Health. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health. Accessed March 6, 2015.

5Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The Social Determinants of Health: Coming of Age. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:381-98. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21091195. Accessed February 11, 2015.

6Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization Web Site. http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/. Accessed February 11, 2015.

7About the Program. County Health Rankings & Roadmaps Web Site. http://www.countyhealthrankings.org/about-project. Accessed February 11, 2015.

8Goldstein D, Holmes J. 2011 Physicians’ Daily Life Report. Harris Interactive. Prepared for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. November 15, 2011. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/web-assets/2011/11/2011-physicians--daily-life-report. Accessed February 11, 2015.