Crysta Jarczynski, MPH

Population Health Service Fellow

City of Milwaukee Health Department

Office of Violence Prevention

Milwaukee, WI

I began my 5th month of the Fellowship at the American Public Health Association 141st Annual Meeting and Exposition in Boston, MA. I was thrilled to find myself back in town exactly 6 months after relocating to Wisconsin. While there, I attended sessions on gender-focused views of sexual health, dimensions of intimate partner violence, social determinants of family violence, and sexual/reproductive health issues among adolescents. Over the course of the meeting, it became clear that when public health professional are talking about sex, they’re usually talking about preventing harm in sex. Most of conversations focused on violence, STI’s, unwanted pregnancy, and human trafficking - all very important issues to treat and prevent. But at some point during my second day, I couldn’t help but think, “When did sex and sexuality become so inherently negative?”

These topics are important and often leave me feeling troubled about the state of sexual health in our country and around the world. However, there were some presenters who brought me back to a hopeful place that seemed rich with possibilities. One session was on affirmative models for sexual health, which included discussions about teaching positive sexuality (communication, pleasure, and consent) as a way to prevent the harm that can accompany intimate relationships. The silence around sexuality in our communities undoubtedly increases the silence around negative sexual experiences. If we don’t talk about sex, we don’t talk about bad sex. This session reminded me that there should be a place in our prevention recommendations for affirmative discussions about sexuality. This could take form in many ways, including pushing for more comprehensive sex education in schools and developing community-based curricula for teens and young adults.

I was also excited about a

presentation by Paul J. Fleming, MPH about unintentional constructions of

gender in public health interventions.

Mr. Fleming deconstructed the “Man Up Monday” campaign as an example. The campaign is responsible for doubling the

rates of STI testing among young males in Virginia and it received an award from

the APHA last year. Mr. Fleming was

gracious about the success of the campaign, but he pointed out that the

marketing techniques utilize a traditional view of masculinity that promotes

harmful gender norms. “Man Up Monday” is

a male-focused public health approach that operates on one idea of what it

means to be a young man - specifically, highlighting “hook ups” as the primary

form of intimacy for young men. Mr. Fleming charged the audience to work to incorporate gender-transformative approaches into our public health work. Gender-transformative techniques reach out to a specific gender while simultaneously challenging society’s idea of what it means to identify as that gender. A good example of this approach is Program H, which uses activities to teach groups of young men (ages 15-24) about gender, sexuality, reproductive health, fatherhood, violence prevention, emotional health, drug use, and living with HIV.

I was also excited about a

presentation by Paul J. Fleming, MPH about unintentional constructions of

gender in public health interventions.

Mr. Fleming deconstructed the “Man Up Monday” campaign as an example. The campaign is responsible for doubling the

rates of STI testing among young males in Virginia and it received an award from

the APHA last year. Mr. Fleming was

gracious about the success of the campaign, but he pointed out that the

marketing techniques utilize a traditional view of masculinity that promotes

harmful gender norms. “Man Up Monday” is

a male-focused public health approach that operates on one idea of what it

means to be a young man - specifically, highlighting “hook ups” as the primary

form of intimacy for young men. Mr. Fleming charged the audience to work to incorporate gender-transformative approaches into our public health work. Gender-transformative techniques reach out to a specific gender while simultaneously challenging society’s idea of what it means to identify as that gender. A good example of this approach is Program H, which uses activities to teach groups of young men (ages 15-24) about gender, sexuality, reproductive health, fatherhood, violence prevention, emotional health, drug use, and living with HIV. |

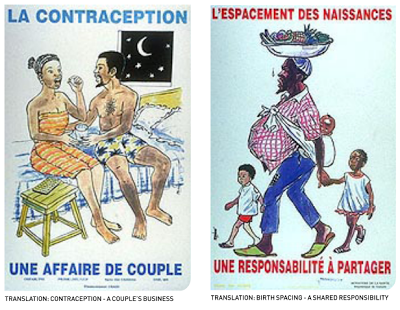

| An example of a gender-transformative health campaign. These posters redefine family planning as a joint responsibility for couples. |

|

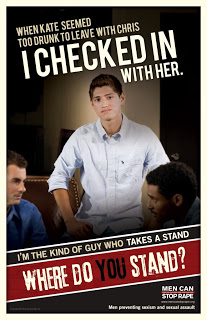

| This ad campaign from Men Can Stop Rape redefines masculinity to include taking a stand against sexual assault. |

I’m currently conducting a

Community Readiness Assessment on the issue of sexual assault in

Milwaukee. For this project, I will be

interviewing close to 80 individuals in the city, from community members to

professionals, to get a multi-faceted picture of sexual assault concerns,

knowledge, and resources in Milwaukee.

The tool then identifies the “level of readiness,” from no awareness to a high level of community ownership, and provides goals and strategies

appropriate for each stage. Once the

level of readiness is established, we will tailor the goals and recommendations

to our city. I’m excited to pull the

perspectives I learned on affirmative sexuality and gender-transformative

approaches to masculinity into the discussion.

When strategizing to prevent and treat sexual assault, it is easy to fragment

the problem because it is multi-layered and everyone’s experience is deeply

personal. However, there are broad

cultural and societal ideas that contribute to the normalization of sexual

violence. While we work to provide

survivor-centered resources that fit each individual’s needs, we have a

parallel mission to combat rape-supportive cultural norms.

Discussions about healthy sexuality and harmful gender roles are essential pieces

of this mission.