Carly Hood, MPA, MPH

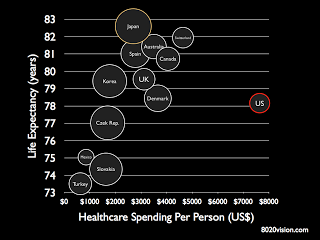

Looking globally, the United States (US) doesn’t fair incredibly well on a number of indicators. Research shows we rank last for female life expectancy and second to last for males compared to most other Western industrialized countries. Furthermore, comparing the US to 17 countries of similar development and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rankings, the US has more years of life lost due to a number of causes: communicable and nutritional conditions, drug related causes, prenatal conditions, injuries, cardiovascular disease and other non-communicable diseases.

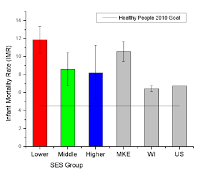

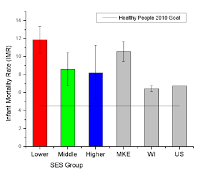

Closer to home, we can compare how Milwaukee, Wisconsin

specifically lies in relation to the rest of the state and the US in general on

a number of indicators. The Milwaukee

Health Report shows that the city has a much higher rate of infant

mortality compared to both Wisconsin and the US. When divided by social and

economic status (SES), you can see that those in the lower SES group have

higher rates than both middle and high SES categories. And the report

shows similar trends for smoking rates, sexually transmitted diseases, dental

visits, cancer screening practices, teen birth rates, violent assault, social

support, lead poisoning, access to healthy foods, uninsured adults and obesity

rates. Milwaukee fairs worse in all of these areas compared to both Wisconsin

and the US.

Closer to home, we can compare how Milwaukee, Wisconsin

specifically lies in relation to the rest of the state and the US in general on

a number of indicators. The Milwaukee

Health Report shows that the city has a much higher rate of infant

mortality compared to both Wisconsin and the US. When divided by social and

economic status (SES), you can see that those in the lower SES group have

higher rates than both middle and high SES categories. And the report

shows similar trends for smoking rates, sexually transmitted diseases, dental

visits, cancer screening practices, teen birth rates, violent assault, social

support, lead poisoning, access to healthy foods, uninsured adults and obesity

rates. Milwaukee fairs worse in all of these areas compared to both Wisconsin

and the US.

Honing in a bit more on the social determinants of health, we know that employment gives working individuals an opportunity provide their

families with nutritious food, educational opportunities, and healthy living

situations. There is a clear

relationship between employment and health—life expectancy for male workers

has risen 6 years for those in the high income brackets, but only 1.3 years for

those in the bottom income brackets. Employment translates directly to income, and we know

the wealthier you are the healthier you are likely to be. Not only are high

income individuals more likely to have insurance and medical care, but also have

better access to nutritious food, opportunities to be physically active, ability

to live in safe homes and neighborhoods, and feel less

stress associated with obtaining these things.

Honing in a bit more on the social determinants of health, we know that employment gives working individuals an opportunity provide their

families with nutritious food, educational opportunities, and healthy living

situations. There is a clear

relationship between employment and health—life expectancy for male workers

has risen 6 years for those in the high income brackets, but only 1.3 years for

those in the bottom income brackets. Employment translates directly to income, and we know

the wealthier you are the healthier you are likely to be. Not only are high

income individuals more likely to have insurance and medical care, but also have

better access to nutritious food, opportunities to be physically active, ability

to live in safe homes and neighborhoods, and feel less

stress associated with obtaining these things.

This is interesting in and of itself, but when we take a

step back, these problems don’t stop with the individual. They are perpetual

and impact families generation to generation. Models increasingly show if you

grow up in a low income house you are less likely to have access to education—amongst

other things—which in turn decreases your opportunity for higher paying

employment, ultimately starting the cycle over. An emerging body of research

suggests that inequality of income makes family background play a stronger role

in determining the outcomes of young people than their own “hard” work (what

does this say about the bootstrap story we tell ourselves??) Inter-generational

earnings mobility is low in countries with high income inequality—Italy, the

United Kingdom, and the US—and is much higher in the Nordic countries, where income

is distributed more evenly. The media is finally picking up on this, and

more studies continue to link poor health outcomes in the long run to

stressors associated with poverty at a young age. I believe it’s the cyclical

nature of this issue that has increased the inequality gaps in our country over

the last forty decades. Once you’re stuck in a lower education or lower income

bracket, it becomes that much more difficult for you to get out.

This is interesting in and of itself, but when we take a

step back, these problems don’t stop with the individual. They are perpetual

and impact families generation to generation. Models increasingly show if you

grow up in a low income house you are less likely to have access to education—amongst

other things—which in turn decreases your opportunity for higher paying

employment, ultimately starting the cycle over. An emerging body of research

suggests that inequality of income makes family background play a stronger role

in determining the outcomes of young people than their own “hard” work (what

does this say about the bootstrap story we tell ourselves??) Inter-generational

earnings mobility is low in countries with high income inequality—Italy, the

United Kingdom, and the US—and is much higher in the Nordic countries, where income

is distributed more evenly. The media is finally picking up on this, and

more studies continue to link poor health outcomes in the long run to

stressors associated with poverty at a young age. I believe it’s the cyclical

nature of this issue that has increased the inequality gaps in our country over

the last forty decades. Once you’re stuck in a lower education or lower income

bracket, it becomes that much more difficult for you to get out.

In recent months, the medical associations of both Canada and Australia have called for a focus on the social determinants and poverty as focus for both medical professionals and policy work, clearly recognizing health should be considered beyond the clinic and hospital (watch an amazing 3 minute clip of Canada’s political perception on health). Here in the US we are still myopically funding medical services rather than the upstream drivers of health which would have the greatest impact on outcomes and equity.

Population Health Service Fellow

Wisconsin Center for Health Equity

Health First Wisconsin

Wisconsin Division of Public Health

Madison, Wisconsin

Looking globally, the United States (US) doesn’t fair incredibly well on a number of indicators. Research shows we rank last for female life expectancy and second to last for males compared to most other Western industrialized countries. Furthermore, comparing the US to 17 countries of similar development and Gross Domestic Product (GDP) rankings, the US has more years of life lost due to a number of causes: communicable and nutritional conditions, drug related causes, prenatal conditions, injuries, cardiovascular disease and other non-communicable diseases.

Closer to home, we can compare how Milwaukee, Wisconsin

specifically lies in relation to the rest of the state and the US in general on

a number of indicators. The Milwaukee

Health Report shows that the city has a much higher rate of infant

mortality compared to both Wisconsin and the US. When divided by social and

economic status (SES), you can see that those in the lower SES group have

higher rates than both middle and high SES categories. And the report

shows similar trends for smoking rates, sexually transmitted diseases, dental

visits, cancer screening practices, teen birth rates, violent assault, social

support, lead poisoning, access to healthy foods, uninsured adults and obesity

rates. Milwaukee fairs worse in all of these areas compared to both Wisconsin

and the US.

Closer to home, we can compare how Milwaukee, Wisconsin

specifically lies in relation to the rest of the state and the US in general on

a number of indicators. The Milwaukee

Health Report shows that the city has a much higher rate of infant

mortality compared to both Wisconsin and the US. When divided by social and

economic status (SES), you can see that those in the lower SES group have

higher rates than both middle and high SES categories. And the report

shows similar trends for smoking rates, sexually transmitted diseases, dental

visits, cancer screening practices, teen birth rates, violent assault, social

support, lead poisoning, access to healthy foods, uninsured adults and obesity

rates. Milwaukee fairs worse in all of these areas compared to both Wisconsin

and the US.

Despite these wide differences, as a country the US spends

more on health care than any other country in the world: nearly $8000 per

person on average!! It is clear many countries achieve higher life expectancy rates with much lower

spending.

One reason for this—and very politically charged currently—may

be that the United States lacks universal health insurance coverage. Our health

system has a weaker foundation in primary care and greater barriers to

affordable care. This lack of access to primary and prevention services means

US patients are more likely than those in other countries to require emergency

department visits or readmissions after hospital discharge…which ultimately

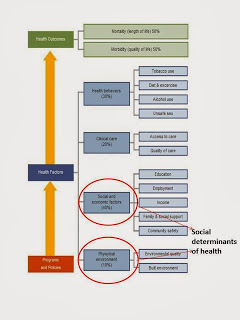

increases costs. But health is determined by more than health care. And I would

argue this is a small piece of the larger puzzle we need to be considering.

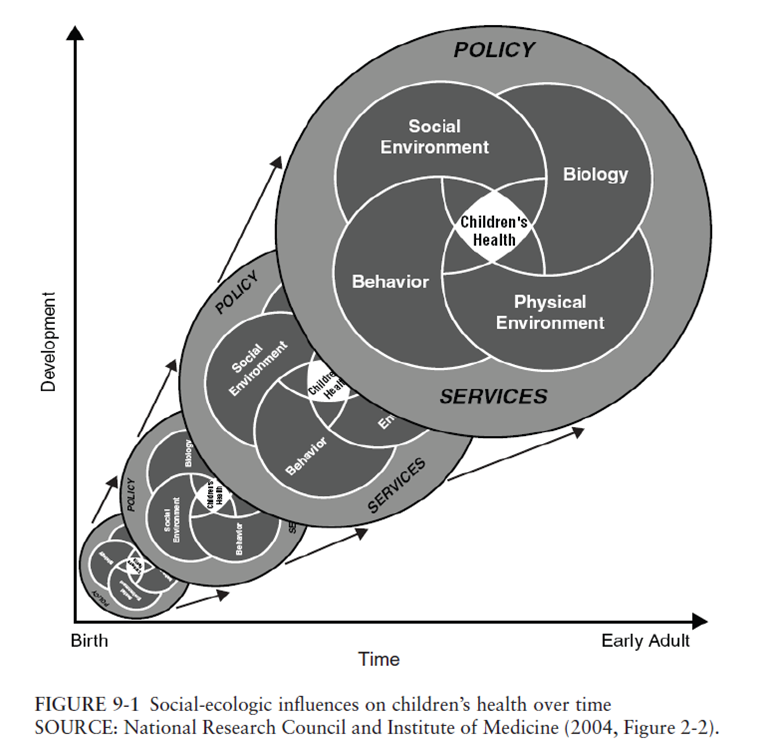

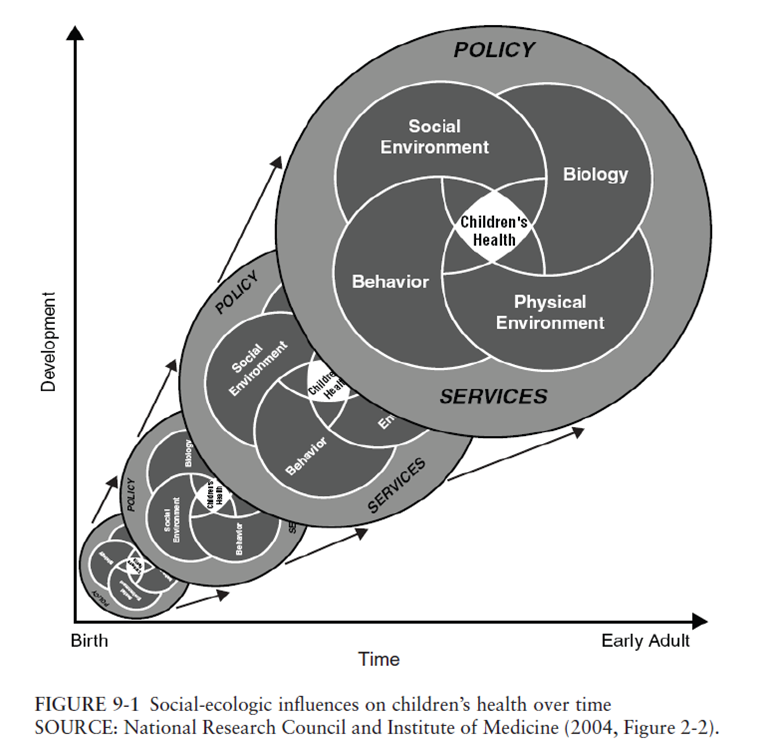

Literature

continues to show that 40% of health outcomes are driven by social and economic

factors and 10% by our physical environment. That means that nearly half of health

outcomes are a result of what we call the social determinants of health. This

includes things like poverty/income, education, and where we live. Going even further upstream, health and wellbeing

are considered within the context of racism/discrimination, sexism, classism,

and power (this is an entirely amazing

body of literature I would suggest you start reading more about here).

Honing in a bit more on the social determinants of health, we know that employment gives working individuals an opportunity provide their

families with nutritious food, educational opportunities, and healthy living

situations. There is a clear

relationship between employment and health—life expectancy for male workers

has risen 6 years for those in the high income brackets, but only 1.3 years for

those in the bottom income brackets. Employment translates directly to income, and we know

the wealthier you are the healthier you are likely to be. Not only are high

income individuals more likely to have insurance and medical care, but also have

better access to nutritious food, opportunities to be physically active, ability

to live in safe homes and neighborhoods, and feel less

stress associated with obtaining these things.

Honing in a bit more on the social determinants of health, we know that employment gives working individuals an opportunity provide their

families with nutritious food, educational opportunities, and healthy living

situations. There is a clear

relationship between employment and health—life expectancy for male workers

has risen 6 years for those in the high income brackets, but only 1.3 years for

those in the bottom income brackets. Employment translates directly to income, and we know

the wealthier you are the healthier you are likely to be. Not only are high

income individuals more likely to have insurance and medical care, but also have

better access to nutritious food, opportunities to be physically active, ability

to live in safe homes and neighborhoods, and feel less

stress associated with obtaining these things.  This is interesting in and of itself, but when we take a

step back, these problems don’t stop with the individual. They are perpetual

and impact families generation to generation. Models increasingly show if you

grow up in a low income house you are less likely to have access to education—amongst

other things—which in turn decreases your opportunity for higher paying

employment, ultimately starting the cycle over. An emerging body of research

suggests that inequality of income makes family background play a stronger role

in determining the outcomes of young people than their own “hard” work (what

does this say about the bootstrap story we tell ourselves??) Inter-generational

earnings mobility is low in countries with high income inequality—Italy, the

United Kingdom, and the US—and is much higher in the Nordic countries, where income

is distributed more evenly. The media is finally picking up on this, and

more studies continue to link poor health outcomes in the long run to

stressors associated with poverty at a young age. I believe it’s the cyclical

nature of this issue that has increased the inequality gaps in our country over

the last forty decades. Once you’re stuck in a lower education or lower income

bracket, it becomes that much more difficult for you to get out.

This is interesting in and of itself, but when we take a

step back, these problems don’t stop with the individual. They are perpetual

and impact families generation to generation. Models increasingly show if you

grow up in a low income house you are less likely to have access to education—amongst

other things—which in turn decreases your opportunity for higher paying

employment, ultimately starting the cycle over. An emerging body of research

suggests that inequality of income makes family background play a stronger role

in determining the outcomes of young people than their own “hard” work (what

does this say about the bootstrap story we tell ourselves??) Inter-generational

earnings mobility is low in countries with high income inequality—Italy, the

United Kingdom, and the US—and is much higher in the Nordic countries, where income

is distributed more evenly. The media is finally picking up on this, and

more studies continue to link poor health outcomes in the long run to

stressors associated with poverty at a young age. I believe it’s the cyclical

nature of this issue that has increased the inequality gaps in our country over

the last forty decades. Once you’re stuck in a lower education or lower income

bracket, it becomes that much more difficult for you to get out.

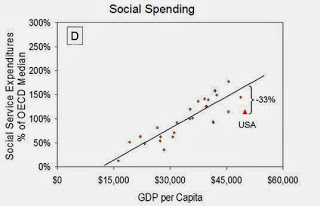

So we know that things like education and income seriously

impact health outcomes. But as a nation we are highest in

poverty rates and third to last in educational rates compared to similarly

developed countries. Social policies, or a lack thereof, show what a country

prioritizes and how they fund those priorities. The US ranks second

to last in social benefits—support with sickness, unemployment, retirement,

housing, education and family circumstance—and some of the countries with the

best health outcomes rank the highest in terms of social transfers. Health

policy experts have

noted how easy it is to “connect the dots from inadequate social spending

to excess poverty and income inequality to more chronic illness and higher

health care spending.”

In recent months, the medical associations of both Canada and Australia have called for a focus on the social determinants and poverty as focus for both medical professionals and policy work, clearly recognizing health should be considered beyond the clinic and hospital (watch an amazing 3 minute clip of Canada’s political perception on health). Here in the US we are still myopically funding medical services rather than the upstream drivers of health which would have the greatest impact on outcomes and equity.

How we choose to live reflects both the citizen and consumer

in all of us; we are each at once a citizen who supports our individual and

community well-being, and a consumer who seeks cheap prices and large returns

on our investments. For decades we’ve let our inner consumer

speak louder than our inner citizen, and this has resulted in increased

deregulation and financialization, threatened wages and working conditions, falling

taxes (and ergo less support for a plethora of public services), and increasing

environmental degradation. And while we’ve listened to the consumer voice and voted

this way for the benefit of ourselves and our families, whether knowing it or

not, these decisions have had the greatest impact on the health and wellbeing

of the poor, people of color, and marginalized groups around the world. Inequality

is a choice however, as noted recently by Nobel economist Joseph Stiglitz. To

him, we are entering a world divided not just between the haves and have-nots,

but also between those countries that do nothing about it, and those that do. I

couldn’t agree more.

It’s clear the dominant narrative we’ve told ourselves as a

society is one supportive of individual behavior, personal choice, freedom and strong

work ethic. Unfortunately, the data show this doesn’t seem to be producing a

particularly equal, healthy and productive population. And while creating a

more equitable society has

benefits for economic growth and cost savings, that shouldn’t be the only rationale

we use in an attempt to create solid social policy. It’s ok for the rationale to be about the moral obligation we have to create

opportunity for all to lead healthy lives; it should be about nurturing the relationships and connections we

foster in our families and communities; living on a planet we are proud to

leave to our children; finding support in every environment in which we exist—our

homes, schools, and places of work; and it

should be about sewing the safety nets that catch any of us who might occasionally fall. In the United States, we can and should be rewriting the narrative so that our dominant societal view

is one which reflects these ambitions, not just coping with the “individualist”

story we’ve read to ourselves for so long.